The “Sweet Spot”: How to Avoid Running Injuries and Find Your Fast on the Run

The human body is incredible! When exposed to a load, our tissue adapts to the demand that we are putting on it. This explains how holding a given pace over a distance that once seemed impossible is now a breeze, or how you can easily knock off way more reps of your glute strengthening exercises after months of diligent training. You expose your tissue to a load, it adapts, and you get stronger.

But if that’s the case, why is it that you keep getting injured every time that you ramp up your training? Why do those darn hip thrusters never feel any easier?

Finding the “Sweet Spot”

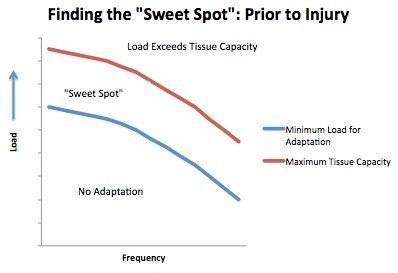

A key concept in building fitness while preventing and managing injury is balancing training load with your body’s capacity to tolerate the demand. In order to build a tissue’s capacity to tolerate a greater load, you must expose it to a demand large enough to stimulate adaptation. At the same time, if you exceed the capacity of a tissue, you’ll be knocked down by injury.

Imagine you were trying to improve your 5k time by running an easy 5k run a few times a week. Go too easy and you’ll never get stronger. Your training might be enough to maintain your previous 5k race time, but it certainly isn’t going to be your ticket to a new personal best. Instead, if you added in some strength training, speed work and other workouts specific to your goal, you would be far more likely to create the physiological adaptations required for you to be able to hold a faster pace for the entire 5 km (and to avoid injury while you’re a it). A minimum load or demand is required to promote adaptations such as improved strength, fitness and tissue healing.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, if you overload a tissue or increase the demand that you are putting on it faster than it is capable of adapting, you’ll end up injured. Regardless of the type of injury that we see, they all have one very important thing in common: the demand on a tissue has exceeded the capacity of that tissue to handle the load.

Our goal in managing literally every injury that we see (and preventing them in the first place!) is to understand and work within the balance of training load and the tolerance of the tissue being loaded. Simply put, we must find our individual “sweet spot” of working hard without pushing our bodies beyond what they are able to cope with.

Constantly Evolving

One of the trickiest things about finding your “sweet spot” for tissue adaptation is that it is constantly changing. As you get stronger, the load required to stimulate adaption is higher. As you start training again after taking time off, the load that might push you over the edge of injury is lower than it may have been when you were race ready a few months ago.

The “sweet spot” is individual and constantly evolving as your fitness, training patterns, goals and age change.

One complaint that we commonly hear from runners returning from injury is that the demand that they are putting on their body is way less than it once was and, a) the pain is back despite the reduced load, or, b) they feel phenomenal and are desperate to jump right back into their training plan and strength routine as though the injury had never happened.

In both of these cases, it’s important to consider that a tissue’s capacity to tolerate a load is reduced following injury. Following an injury, the “sweet spot” shifts so that a load that was once well within the perfect range for adaptation is now sufficient to overload the tissue and create an inflammatory response. The capacity of the injured tissue is reduced and will need to be gradually built up again. This is one of the main drivers behind injury recurrence; athletes returning from injury frequently jump back into their training regimen without allowing time to gradually adapt to the training load once again. This also explains why a previous injury is one of the best predictors of future injury.

Following injury, the “sweet spot” shifts and the load required to create tissue adaptation is reduced. Similarly, the maximum load that our tissue can tolerate is reduced. (Adapted from Dye, 2015). or that range of loading applied across the joint that is compatible with and probably inductive of maintenance of tissue homeostasis or that range of loading applied across the joint that is compatible with and probably inductive of maintenance of tissue homeostasis.

Figure 1: If the load on a tissue is too low, no adaptation occurs. If it is too high, the load exceeds the capacity of the tissue, leading to injury. Our goal is to work in the “sweet spot” which allows adaptation without injury.

How to Manage Training Load

The first step to finding your “sweet spot” for tissue adaptation is understanding the factors that determine the amount of load that you put on a tissue. These include:

How much you train (volume)

How hard you train (intensity)

How often you train (frequency)

The type of training (ie. Cycling vs running)

When it comes to injury prevention and recovery, it is important to remember that any increases in your training load must come gradually. Remember that soft tissue, such as muscles, tendons, and ligaments, will adapt much more slowly than your cardiovascular fitness and be cautious with how quickly you increase the demand.

A couple of general reminders that we often give to people as they look to ramp up their training:

Remember not to increase too many components of your training at a time. For example, if you are adding an extra run each week, you shouldn’t also make each run longer and faster.

While having a goal for every workout is important, you do not need to work at a high intensity every time that you train. Your weekly easy to moderate workouts should outnumber your high intensity workouts.

Don’t forget to allow yourself time to recover. This may mean that you build your training load for a few weeks, and then build in a lighter recovery week in order to give your body a break. It might also mean giving yourself an offseason where you focus more on cross training to make sure that you are as strong as possible as you enter your next training phase. No one can maintain 100% race ready fitness all the time!

The 10% rule is the real deal. You should aim to increase the demand on your body by about 10% a week. If you were previously running 10 km, and you jump right to 20 km, you are potentially overloading your tissue and opening yourself up to injury.

Look At the Big Picture

It goes without saying that individual tissues do not work in isolation. For example, knee pain is often driven by limited strength and mobility in the hips and ankle. If you focus only on building tolerance for a given load around the knee while ignoring the ankle and hip, that too will increase the likelihood of injury. This is often where an assessment from a physiotherapist or chiropractor may be helpful. Both are professionals who are highly trained in assessing function, mobility and movement patterns that may be contributing to your injuries.

Our Building Better Runners program is also designed specifically to help identify and minimize any weaknesses or abnormal movement patterns that may lead to tissue overload anywhere in the kinetic chain from your toes all the way through your ankles, knees, hips, back and upper body. Often, identifying and addressing issues that may lead to injury via tissue overload can also help you to run longer and faster. Mission accomplished!

References:

Dye, S. The Pathophysiology of Patellofemoral Pain: A Tissue Homeostasis Perspective. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2005 Jul;(436):100-10.